Cartile bune pe care le citesti in decursul unei vieti sunt intr-un fel ca prietenii buni, de la care ai tot timpul ceva de invatat, fie despre lume fie despre tine insuti. Dupa ce le citesti ajungi sa le porti cu tine pana la sfarsitul vietii, inca mi se pare incredibil cum pot sa-mi amintesc idei si scene din carti citite acum mai bine de 20 de ani.

Din categoria asta o sa fie cu siguranta si “Zorba, grecul” pe care tocmai am terminat-o de citit, si scriu randurile astea tocmai pentru a incetini voit procesul de uitare. De cum am inceput-o mi-a adus aminte de “Narcis si Gura de Aur” al lui Hesse, una din cartile citite (si recitite) care sus in lista cartilor mele preferate. Temele atinse de amandoua cartile sunt atat de profunde, dar in acelasi timp prezentate intr-un mod atat de natural incat e imposibil sa nu te indragostesti de ele pe masura ce le citesti (da, chiar poti sa te indragostesti si de o carte, in cazul meu a fost una din putinele carti pe care le-am citit cu incetinitorul, nevoind parca sa se termine).

O sa enumar mai jos in nici un fel de ordine speciala lucruri din carte ce sper sa-mi ramana in minte si peste ani: felul in care e pictata prin cuvinte zona rurala in care se desfasoara actiunea romanului cu toate micile personaje ce fac povestea sa curga, nenumaratele momente in care Zorba, prin cuvinte putine si clare, picteaza o viziune asupra vietii pe care nu ai cum sa nu o iubesti, opozitia dintre Zorba si Narator, opozitie ce e intr-un fel in oricare din noi si faptul ca sunt multe lucruri din ceea ce inseamna sa fii om ce nu pot fi transpunse in cuvinte. Nu intru mai mult in detalii si sunt convins ca la un moment o sa recitesc cartea, sunt prea multe pasaje cu care am rezonat atunci cand le-am citit si pe care din pacate nu le-am notat cum trebuie.

Mai voiam sa mai adaug ca singurul neajuns al cartii e ca are o tenta usor misogina pe alocuri, lucru intr-un fel de inteles tinand cont de perioada si personajele pictate, eu am putut sa traiesc cu ea, dar sunt curios ce parere o sa aiba si Mihaela dupa ce o citeste.

Acum voiam sa vad si filmul, sunt convins ca Anthony Quinn joaca rolul vietii lui in film dar intr-un fel mi-e frica ca imaginile personajelor si locurilor create de mintea mea vor fi inlocuite de modul imperfect in care pot fi imortalizate pe film. Dar cred ca pot sa traiesc si cu sacrificiul asta. Cartea am ascultat-o in engleza, fara audiobook-uri nu stiu daca as fi apucat sa citesc ce am citit pana acum anul asta.

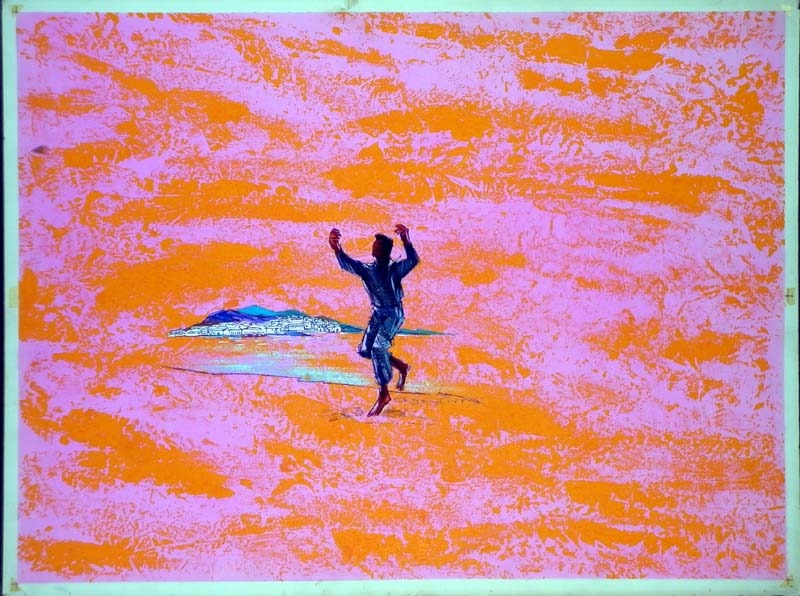

Am vrut sa aleg un citat din capitolul despartirii si pana la urma am pus mai jos tot capitolul, din ce am citit pana acum e cea mai fain pictata scena de despartire din tot ce am citit pana acum.

Take a good look at him; never, never again will you set eyes on Zorba!

I could have thrown myself upon his old bosom and wept, but I was ashamed. I tried to laugh to hide my emotion, but I could not. I had a lump in my throat. I looked at Zorba as he craned his neck like a bird of prey and drank in silence. I watched him and I reflected what a truly baffling mystery is this life of ours. Men meet and drift apart again like leaves blown by the wind; your eyes try in vain to preserve an image of the face, body or gestures of the person you have loved; in a few years you do not even remember whether his eyes were blue or black. The human soul should be made of brass; it should be made of steel! I cried within me. Not just of air!

Zorba was drinking, holding his big head erect, motionless. He seemed to be listening to steps approaching in the night or retreating into the innermost depths of his being. ‘What are you thinking about, Zorba?’

‘What am I thinking about, boss? Nothing. Nothing, I tell you! I wasn’t thinking of anything.’

After a moment or two, filling up his glass again, he said: ‘Good health, boss!’

We clinked glasses. We both knew that so bitter a feeling of sadness could not last much longer. We would have to burst into tears or get drunk, or begin to dance like lunatics. ‘Play, Zorba!’ I suggested.

‘Haven’t I already told you, boss? The santuri needs a happy heart. I’ll play in a month’s, perhaps two months’ time – how can I tell? Then I’ll sing about how two people separate for ever.’

‘For ever!’ I cried terrified. I had been saying that irremediable word to myself, but had not expected to hear it said out loud. I was frightened.

‘For ever!’ Zorba repeated, swallowing his saliva with some difficulty. ‘That’s it – for ever. What you’ve just said about meeting again, and building our monastery, all that is what you tell a sick man to put him on his feet. I don’t accept it. I don’t want it. Are we weak like women to need cheering up like that? Of course we aren’t. Yes, it’s for ever!’

‘Perhaps I’ll stay here with you … ‘ I said, appalled by Zorba’s desperate affection for me. ‘Perhaps I shall come away with you. I’m free.’ Zorba shook his head.

‘No, you’re not free,’ he said. ‘The string you’re tied to is perhaps longer than other people’s. That’s all. You’re on a long piece of string, boss; you come and go, and think you’re free, but you never cut the string in two. And when people don’t cut that string …’

Til cut it some day!’ I said defiantly, because Zorba’s words had touched an open wound in me and hurt.

‘It’s difficult, boss, very difficult. You need a touch of folly to do that; folly, d’you see? You have to risk everything! But you’ve got such a strong head, it’ll always get the better of you. A man’s head is like a grocer; it keeps accounts: I’ve paid so much and earned so much and that means a profit of this much or a loss of that much! The head’s a careful little shopkeeper; it never risks all it has, always keeps something in reserve. It never breaks the string. Ah no! It hangs on tight to it, the bastard! If the string slips out of its grasp, the head, poor devil, is lost, finished! But if a man doesn’t break the string, tell me, what flavour is left in life? The flavour of camomile, weak camomile tea! Nothing like rum – that makes you see life inside out!’

He was silent, helped himself to some more wine, but started to speak again.

‘You must forgive me, boss/ he said. Tm just a clodhopper. Words stick between my teeth like mud to my boots. I can’t turn out beautiful sentences and compliments. I just can’t. But you understand, I know.’

He emptied his glass and looked at me.

‘You understand!’ he cried, as if suddenly filled with anger.

‘You understand, and that’s why you’ll never have any peace. If you didn’t understand, you’d be happy! What d’you lack? You’re young, you have money, health, you’re a good fellow, you lack nothing. Nothing, by thunder! Except just one thing – folly! And when that’s missing, boss, well…’

He shook his big head and was silent again.

I nearly wept. All that Zorba said was true. As a child I had been full of mad impulses, superhuman desires, I was not content with the world. Gradually, as time went by, I grew calmer. I set limits, separated the possible from the impossible, the human from the divine, I held my kite tightly, so that it should not escape. A large shooting-star streaked across the sky. Zorba started and opened wide his eyes as if he were seeing a shooting-star for the first time in his life.

‘Did you see that star?’ he asked.

‘Yes.’

We were silent.

Suddenly Zorba craned his scraggy neck, puffed out his chest and gave a wild, despairing cry. And immediately the cry canalised itself into human speech, and from the depths of Zorba’s being rose an old monotonous melody, full of sadness and solitude. The heart of the earth itself split in two and released the sweet, compelling poison of the East. I felt inside me all the fibres still linking me to courage and hope slowly rotting.

Iki kiklik bir tepende otiyor Otme de, kiklik, bemin dertim yetiyor, amanl amanl

Desert, fine sand, as far as eye can see. The shimmering air, pink, blue, yellow; your temples bursting. The soul gives a wild cry and exults because no cry comes in response. My eyes filled with tears.

A pair of red-legged partridges were piping on a hillock; Partridges, pipe no morel My own suffering is enough for me, amanl amanl.

Zorba was silent. With a sharp movement of his fingers he wiped the sweat off his brow. He leaned forward and stared at the ground.

‘What is that Turkish song, Zorba?’ I asked after a while.

‘The camel-driver’s song. It’s the song he sings in the desert. I hadn’t sung it or remembered it for years. But just now …’

He raised his head, his voice was sharp, his throat constricted.

‘Boss,’ he said, ‘it’s time you went to bed. You’ll have to get up at dawn tomorrow if you’re going to catch the boat at Candia. Good night!’

I’m not sleepy,’ I said. Tm going to stay up with you. This is our last night together.’ “That’s just why we must end it quickly!’ he cried, turning down his empty glass as a sign he did not wish to drink any more. ‘Here and now, just like that. As men cut short smoking, wine, and cards. Like a Greek hero, a Palikari.

‘My father was a real Palikari. Don’t look at me, I’m only a breath of air beside him. I don’t come up to his ankles. He was one of those ancient Greeks they always talk about. When he shook your hand he nearly crushed your bones to pulp. I can talk now and then, but my father roared, neighed and sang. There very rarely came a human word out of his mouth.

‘Well, he had all the vices, but he’d slash them, as you would with a sword. For instance, he smoked like a chimney. One morning he got up and went into the fields to plough. He arrived, leaned on the hedge, pushed his hand into his belt for his tobacco-pouch to roll a cigarette before he began work, took out his pouch and found it was empty. He’d forgotten to fill it before leaving the house. ‘He foamed with rage, let out a roar, and then bounded away towards the village. His passion for smoking completely unbalanced his reason, you see. But suddenly – I’ve always said I think man’s a mystery – he stopped, filled with shame, pulled out his pouch and tore it to shreds with his teeth, then stamped it in the ground and spat on it. “Filth! Filth!” he bellowed. “Dirty slut!”

‘And from that hour, until the end of his days, he never put another cigarette between his lips.

‘That’s the way real men behave, boss. Good night!’ He stood up and strode across the beach. He did not look back once. He went as far as the fringe of the sea and stretched himself out there on the pebbles. I never saw him again.

Leave a Reply